It was well known that Mr. Stillwell, the Headmaster at the Lefferts School had a dog’s jaw. He had his own jaw shot off in the war, and the field medical unit had the presence of mind and the skill to sacrifice Jeff, Charlie Company’s mascot and mine sniffer German Shepherd, and do quick reconstructive surgery. He was immediately evacuated to King’s Hospital, Margate, where he would be further operated on.

The surgeons, however, were surprised to see that Jeff’s jaw had knit almost perfectly. Apparently Stillwell’s musculature, tendons, and ligaments had miraculously survived the Nazi mortar round. The shard of hot steel had shattered his lower jaw completely, but somehow he was left with a lot of wet, dangling, but still useful flesh. The surgeons decided to leave well enough alone.

Headmaster Stillwell made his rounds about campus, greeted the students as they filed into chapel, met their parents, and cheered on the football team on against Choate, while all anyone could think of was his dog’s jaw.

Twenty-five years later, the school produced a special edition of the Alumni Magazine featuring and honoring Harvey Stillwell for his long and dedicated service. Every student, by then in their 40s, all quickly turned to the article to see if there was anything at all that would give away his secrets and confirm or dispel the rumors that had persisted.

“Beginnings” was the title of the first chapter of the long article on the Headmaster’s life, accompanied by a formal family photo of him and his five brothers taken in Brent Hollow, Kentucky. Lo and behold, all six boys had dog-looking jaws – narrow, under-slung, and weak-looking. So either Harvey simply inherited that simpleton look from his father who in the picture smiled a big toothless smile, or the story of the German mortar and the jaw of Jeff, the German Shepherd was true.

Few of us have looked in the mirror and not wished that our underslung jaws were more prominent, the nose was less so, the eyes further apart or closer together, or the mouth finer and less pronounced. Plastic surgery, that existential game changer, has always been an option, but most of us suspend disbelief, decide that our face has character, strength, or even virtue, and go till the end of days as homely and crudely spun as the day we were born.

One Lefferts alumnus, Saugatuck (Sandy) Flint, looked in the mirror like the rest of us and was discouraged at what he saw, but unlike us who took it in stride and accepted God's strange Creation, he wondered where that stubby nose, prognathous jaw, simian eyes, and prominent ears came from. Fixated on the old photo of the Headmaster's Kentucky family, and obsessed with deconstructing his image in the mirror, he began an exhaustive search through family archives to find the genetic culprits responsible for his sadly misshapen face.

Not that it mattered in the least - what possible good could come from finally knowing that Great Granduncle Hiram had the same closely-set eyes, or that even farther back distant relative Isaiah had his noticeable ears?

Yet there was something important about deciphering oneself, he thought, something indeed existential, and the more he pored through old family photographs and letters written by desperate husbands and wives recalling the features of loved ones, the more he wondered where his more salient, representative, fundamental bits came from - his timidity when it came to mountains but not to girls; his quick to anger over nothing, but his absolute calm and resoluteness when the stock markets crashed or during an earthquake.

Perhaps most importantly, would some of the profound belief from ancestor Phelps Harrington, Puritan pastor of Salem, prosecutor, and man of unquestionably divine inspiration, have come down to him? As it was, he was a religious diffident whose spiritual sentiments clicked at Christmas and Easter but went quiet for the rest of the year.

However, what if there were something to the notion of a religious gene? After all, all human societies had worshipped one thing or another since monkeys came down from the trees and even if his family genes had been crossed and double-crossed over the infinite generational rewiring of DNA resulting in his own desuetude, they might be recoverable.

Why had nature so complicated life by creating every individual so differently? Darwinism went only so far to explain such diversity. The gene pool needed refreshing to survive, but with so many variations? In such cacophony, such irrelevant distinctions, family lineage was the only validating aspect of one's legacy. The 'me' that looked back in the mirror if deciphered logically and traced back to the beginning of one's time, would make more sense that an image made up of nothing but random bits.

One of Sandy's roommates at Yale had had a similar interest in genetic makeup. Because of his long commitment to issues of civil rights and social justice, he wanted to be sure that there were no slave-owning plantation grandees in his past. If it were found that he had some black blood (think Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings, he reminded us), his credentials would be that much more respectable.

Yet to Sandy this missed the point, a historical chimera only with no real destiny or existential import. He was after a more essential genetic legacy, the answer to 'Who am I?'

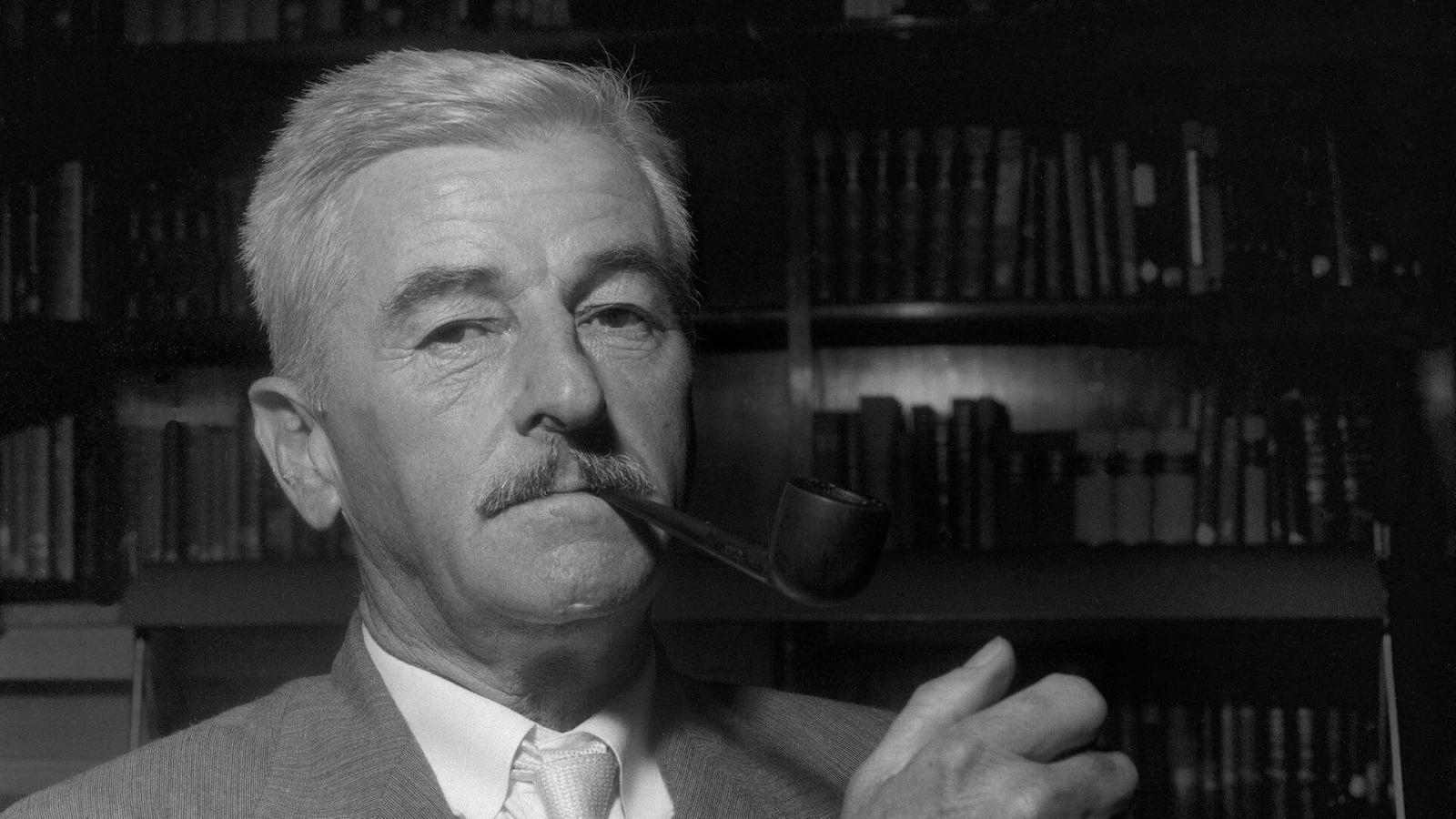

William Faulkner and Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about such legacy. Faulkner's Thomas Sutpen created a mixed race family whose members were obsessed with their parentage, their legitimacy, and their place in the world; and such investigation unearthed truths better left buried. Absalom, Absalom is a book about legacy, family, and origins.

Hawthorne's The House of the Seven Gables is about the permanent influence of the past. The painting of the Pyncheon patriarch hanging on the wall was a reminder to his descendant, Hepzibah, of his corrupt but inescapable legacy. The book is a story about the ineluctable and insistent nature of family history.

Yale used to be a university that understood this well, and for over two centuries it served the families of the New England elite. Legacy admissions were simply an acknowledgement of this sense of tradition and respect for a republican ethos. The offspring of the men who had created America and led it to prosperity and international prominence would never wavered in their sense of responsibility, noblesse oblige, and patriotic duty. While the university might have selected for such traits among a wider pool, it chose to rely on genetic legacy.

Sandy's search of course led nowhere. There were so many interferences in what he thought was a direct lineage - suggested but unknown mistresses, dalliances across every possible social line, marriages far afield from the family's patrician base - that figuring out what was what let alone who he was, was impossible.

Besides, the whole issue had become moot as America had become more than ever a potpourri - lines of caste, class, and family were things of the past. The gene pool had become so indifferently varied and randomly sorted that any genetic search would lead only through a dense, pathless forest.

The face in the mirror that looked back at Sandy Flint as an old man bore little resemblance to that which appeared to him as a young one - family traits were now all but indistinguishable - so it was not surprising that he wondered what all the fuss had been about. A spark of that indeterminate religion clicked again after so long - God's unknowable plan etc. etc. - but age has a way of calming the waters, so he went back to his books, his garden, and his wife of many years.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.