“She was wonderful”, said Abe, “a real gem. An early Christmas present. An unforgettable charm”.

Laura had been thirty-two when they met, Abe sixty-four, stretching the May-December relationship to its outer limits. Abe was reaching the end of his sexual shelf life, and she was in full bloom. He had been surprised that such a woman had any interest in him at all. Yes, he still had much of his hair, was in good health and good physical condition, but as his doctor had advised him, ‘Numbers don’t lie’. In other words it was about time that he began to look more seriously at his end-of-life priorities. Even the best actuarial estimates gave him only relatively few more years, so he had better turn his attention to more important matters.

“Why bother”, Dr. Kaplan had said when he first heard the news. “What will she give you that God won’t?”

It was obvious that Kaplan had never strayed from his marriage of forty years, let alone with a younger woman. Those who had been more adventurous or fortunate knew that they had been extremely lucky. No one wanted to relive their youth – who would want to repeat the adolescent bumbling, the adult mistakes, missed opportunities, and downright shameful episodes of the past? Better done, gone, and forgotten than sifting through the discards to see if there was anything worth retrieving, anything worth a second look.

In Abe’s case, his life had been satisfactory enough – a successful career on K Street, a good marriage, well-placed and respectful children. He never saw cause to wish the genetic cards his son and daughter had been dealt had come from a different deck, or to have chosen a more beautiful wife; or even to have had more affairs. At 70 he was sitting pretty, atop a considerable retirement fund and investment properties, a home in Boca Raton, and good friends.

Yet everything in his life seemed predictable, tired, and worn. A life of no regrets did not mean a life with a happy ending. Encroaching old age was ugly, dispiriting, and frightening. He did not envy the young people around him. He had had his day and it was their time. Nor did he wish that there were some wormhole through which he could be sucked into the past. Youth was overrated, especially when one saw the depressing consequences of disappointments, un-achieved success, illness, bad choices, and bad luck. The years took their toll, and since one could neither go back and fix them, what was the inherent, innate value of youth anyway? Little more than a stop along the way.

Konstantin Levin, a major character in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina saw great irony in God’s having created man - an intelligent, creative, insightful, intuitive, and enterprising being – allowed him to live for a scant few decades, then consign him for all eternity in the cold hard ground of the steppes. If there was no point to life, reasoned Abe, then there was certainly no point to youth. Other than reproduction and carrying capacity of course. On an existential plane, youth was wasted on everyone.

Laura Peterson came into Abe’s life unexpectedly, a work meeting, drinks, a conference in Cairo; dinners, and finally sex. The scenario was not new to Abe. He had always had affairs, but because of circumstances, they were all ‘commensurate’. The women were like him all professionals, travelers, within a few years of age, happily loosed from the fetters of marriage or partnership. There was nothing remarkable or particularly interesting in these short-term relationships. They were almost de rigueur, part of the business traveler’s benefit package, a no-strings-attached rider to one’s contract.

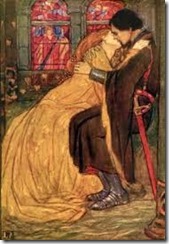

Abe’s love affair with Laura, however, defied the actuarial odds and the lottery. An old man was not supposed win big. He was designed to lie down and take it easy or die in his traces, not get back in the saddle. He knew that eventually she would give up on him for a more expected life; and more importantly would no longer be able to overlook his stoop, his ailing hip, his older children, and his futurelessness. Since Abe had as little enthusiasm for the future as the past, and since consequently the present was the only tasty morsel in the buffet, he gorged himself. His affair with Laura Petersen was right out of a ladies’ library romantic novel.

"Shh," he said, pulling her up so they were face-to-face again. He slid his hands between her legs, positioning fingers and thumb the way she'd taught him. Except that wasn't right. She hadn't taught him. They'd figured it out together, how to make her come. He nuzzled against her, his lips on her neck, nibbling and kissing his way up to her earlobe, where she'd always been ticklish. "Ooh," she whispered. "Ooh! Oh, oh, oh," she sighed, as he worked his fingers against the slick seam . . . and then she forgot to pose, forgot about trying to look good, and lost herself inside her own pleasure. Andy watched her squeeze her eyes shut as she clamped her thighs against his wrist and snapped her hips up, once, twice, three times before she froze, all the muscles in her thighs and belly and bottom tense and quivering, and he felt her contract against his fingers (Jennifer Weiner, Who Do You Love?)He wished he could have felt instead like Cormac McCarthy:

Lying under such a myriad of stars. The sea’s black horizon. He rose and walked out and stood barefoot in the sand and watched the pale surf appear all down the shore and roll and crash and darken again. When he went back to the fire he knelt and smoothed her hair as she slept and he said if he were God he would have made the world just so and no different (The Road)

The problem is that with Abe, like all older men in an affair with a younger woman, it was the pulp fiction that said it all. There were no existential thoughts, no God, no kindness and compassion, just adolescent wet dreams. The rotten prose captured the pure physical responsiveness of the sex act; and that was all that mattered. It was the only reliving of the past that made any sense. It wasn’t reliving a particular event or recreating a circumstance – staying in a familiar hotel, eating in our restaurant – it was playing the part of a youth as an old man, and voila la difference.

Phillip Roth’s character, Coleman Silk, says in The Human Stain, describing his affair with a woman half his age, “Granted, she's not my first love. Granted, she's not my great love. But she is sure as hell my last love. Doesn't that count for something?” Abe was Coleman Silk. “It’s all about the sex, isn’t it?”, asks Silk’s friend; but although Silk denies it and criticizes his much younger friend of his own romantic notions and unfilled sexual demands, it is indeed about the sex. The book has a happy ending only in that Coleman Silk dies without ever having to give up his woman. His last memories are of her body.

“Too soon old, too late schmart”, said Herman after hearing Abe’s story. “You’ll never learn. The putz is not the way to figure things out.”

“Who says I’m trying?”, said Abe.