Yet even so there is but one world and everything that is imaginable is necessary to it. For this world also which seems to us a thing of stone and flower and blood is not a thing at all but is a tale… So everything is necessary. Every least thing. This is the hard lesson. Nothing can be dispensed with. Nothing despised. Because the seams are hid from us, you see. The joinery. The way in which the world is made. We have no way to know what could be taken away. What omitted...Of the telling there is no end." – Cormac McCarthy, The Crossing

McCarthy’s character, however, is no nihilist, and his ‘everything

is necessary’ is far different from Ivan Karamazov’s ‘everything is possible’.

The old man’s reflections are spiritual and profoundly religious. The world,

said the old man, was nothing but witness – tales told by others which define,

delimit, and validate.

He saw the world pass into nothing in the very multiplicity of its instancing. Only the witness stood firm. And the witness to that witness..If the world was a tale, who but the witness could give it life?Where else could it have its being.

This is an interesting take on existential philosophy. On the one

hand it accepts the vanity of identity. Every word we speak is vanity,

the old man says. There can be no absolute truth, no concrete

establishment of reality because the world is nothing but observation. A man or

a stone are nothing but what each observer creates.

On the other hand, because nothing in this subjective world can be

left out, then the world itself has some intelligent cohesion. The world may be

nothing more than a collection of tales, but in its seamlessness, how would

anyone know what to take away?

A nihilist would stop there. The world is made up of random

events set in motion by no divine creator with spiritual purpose. Nietzsche was

the most expressive of this philosophy, saying that the expression of individual

will was the only validation of humanity in a meaningless world.

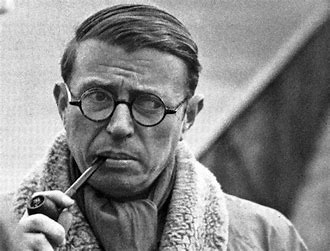

Existentialists like Sartre added positivity – the world may be meaningless, but

one can mitigate the loneliness by right action.

McCarthy could not stop there. A relative, subjective world whose

reality exists only by dint of tales of identity, cannot exist without

substance.

The philosophy of Kierkegaard resembles that expressed by

McCarthy, at least until McCarthy’s final epiphany of grace.

One of Kierkegaard's recurrent themes is the importance of subjectivity, which has to do with the way people relate themselves to (objective) truths. In Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, he argues that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity."

What he means by this is that most essentially, truth is not just a matter of discovering objective facts. While objective facts are important, there is a second and more crucial element of truth, which involves how one relates oneself to those matters of fact. Since how one acts is, from the ethical perspective, more important than any matter of fact, truth is to be found in subjectivity rather than objectivity (Hong, Howard and Edna, The Journals of Soren Kierkegaard, Vol. IV)

Kierkegaard and Sartre agree that subjectivity can be mitigated by

ethical action; but McCarthy goes much farther. Any ‘ethical’ action would have

to be itself subjective – in the eye of the beholder – and therefore of no

absolute meaning.

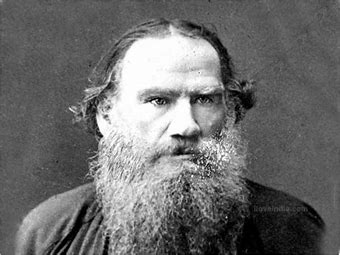

Tolstoy in his treatise on history expounded in the second

Epilogue of War and Peace concludes that not only is reality

subjective, but that it has been so conditioned by past events that no

individual act, no matter how it is perceived, has no objective meaning.

Napoleon’s victories or defeats were less due to his brilliance and military

acumen but by the thousands of random and purposeful events on which these

actions were predicated.

McCarthy’s most unusual and unique insight is about God’s

witness. Does this endless referential relativity stop anywhere, he wonders?

Does it stop with God?

It cannot, he reasoned, because God, the creator of all, stands

alone and apart from those he created. This was the existential

tragedy, said McCarthy – God could have no witness.

Nothing against which He terminated. Nothing by way of which his being could be announced to Him. Nothing to stand apart from and to say I am this and that is other. Where that is I am not. He could create everything save that which would say to him no.

Yet God must exist without witness because without Him, our world

would have no anchor, no meaning, and no substance.

The truth is rather that if there were no God then there could be o witness for there could be no identity in the world but only each man’s opinion of it.

Bear closely with me now, said the old man.

There is another who will hear what you never spoke. Stones themselves are made or air. What they have power to crush never lived. In the end we shall all of us be only what we have made of God. For nothing is real save his grace.

A world of complete subjectivity cannot possibly exist, reasoned

McCarthy. There has to be an existential anchor; one permanent, absolute truth;

one fixed reference point, a spiritual North Star.

The old man says:

For the path of the world also is one and not any and there is no alter course in any least part of it for that course is fixed by God and contains all consequence in the sway of its going and outside of that going there is neither path nor consequence nor anything at all. There never was.

In other words, God created the world with no meaning, purpose, or

consequence; and it is the understanding of that illogical conundrum that is the

essence of faith.

Dostoevsky spent his entire life searching for God and for

meaning. For years he was convinced that science, philosophy, and history might

provide him proof of God’s existence and an anodyne for the despair of

meaninglessness. Yet no objective discipline could satisfy him. Nor could any

of the world’s theologians for, no matter how they relied on logic as Aquinas

and Augustine did, faith was always a matter of subjective belief. In the end,

Tolstoy simply gave up, looked around him, and decided that if billions of

people past and present believed in a Supreme Being, why shouldn’t he?

Constantine Levin in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina dealt with

the same doubts and came to a similar conclusion.

I shall go on in the same way, losing my temper with Ivan thePerhaps the most interesting aspect of McCarthy’s philosophy is his theory of tales. The stories of others define us and give us our identity. In principle there is nothing new in this insight. Authors like Robert Browning (The Ring and the Book), Lawrence Durrell (The Alexandria Quartet) and the filmmaker Kurosawa (Rashomon) all wrote about subjectivity. There is no such thing as reality, they all said, only views of it. Yet McCarthy focuses on the stories people tell, their narratives.

coachman, falling into angry discussions, expressing my opinions

tactlessly; there will be still the same wall between the holy of

holies of my soul and other people, even my wife; I shall still

go on scolding her for my own terror, and being remorseful for

it; I shall still be as unable to understand with my reason why

I pray, and I shall still go on praying; but my life now, my

whole life apart from anything that can happen to me, every

minute of it is no more meaningless, as it was before, but it has

the positive meaning of goodness, which I have the power to put

into it.

Oral traditions in Africa recall history through the retelling of stories. However, because each griot must necessarily be subjective, history itself must gradually if only imperceptibly change over time. Neither the past nor the present is fixed, discernible, and absolute.

Descartes’ ‘I think, therefore I am’ validated personal experience. Everyone might see the world differently, he said, but the fact that each of us sees and reflects on what we see is validation of the the primacy of the individual. Christianity teaches that each of us is endowed by God with a soul – our own special, individual, unique spiritual essence. It is what makes us unique and uniquely responsible for understanding God, his nature, and his purpose. It is what makes us who we are.

McCarthy’s vision, while spiritual, does not explicitly include soul. If anything, it is a Buddhist vision, one of acceptance. The path to enlightenment is one of negation, understanding, and patience.

McCarthy’s cosmology perhaps most closely resembles that of Australian aborigines whose ancestors sang the world into being and who can navigate the world by singing their songs. The world is nothing but evocation of the past and the discovery of it in the present; and stories woven into relationships and their expressions are the only reality.

McCarthy’s stories are themselves compelling. The story of the boy in The Crossing is one of myth, metaphor, philosophy, and native spirituality – and this book, more than any other, is a chronicle of his spiritual quest.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.